Proof Prison Reforms Work: Joel Castón, Inmate who was Given Right to Vote, Became an Elected Official Working from Jail, (and is Finally Free).

The moral of this highly inspirational story is how prison reforms could be a powerful deradicalisation strategy. Though unrelated to terrorism, Joel's journey to redemption, with support from the government, turned a "bad guy" into " a good guy." This story is particularly useful to some African regimes which tend to offer no routes for offenders to become useful members of their societies, hence making them vulnerable to radicalisation.

‘No evidence’ that longer prison sentences will deter terrorists, watchdog warns

Government says package of laws including 14-year minimum term for plotters will ‘keep public safe’

Joel Castón — mentor, leader, @Georgetown Scholar, and ANC Commissioner — is a free man after 27 years of incarceration. Welcome home Joel! pic.twitter.com/SLrouiZ9zp

— Georgetown University Prisons & Justice Initiative (@georgetownpji) November 22, 2021

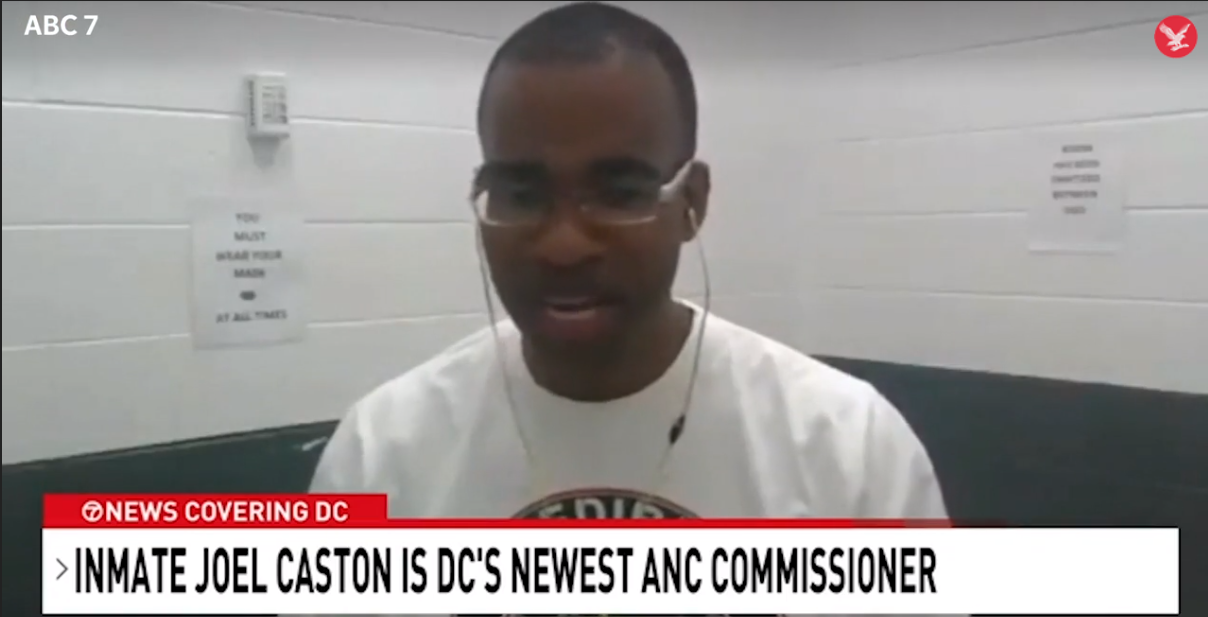

D.C. reforms gave inmates a vote. Now an elected official is working from jail.

Joel Castón is a newly elected city official with a few months left behind bars — the city’s first incarcerated person to win an election.

By Stephanie LaiJuly 25, 2021 at 6:00 a.m. EDT

Joel Castón wakes up in his corner cell before dawn as he has for the last 26 years while incarcerated. The light from the thin rectangular window offers little illumination as he prepares for the day.

He switches the radio to Praise 104.1. Gospel music fills his 5-by-10-foot white-brick room as he reads Psalm 43. He occasionally studies a copy written in French, one of the five languages he picked up while incarcerated.

Standing 6-foot-1 with a smile unbroken by the 16 institutions he’s called home, he neatly makes his bed, removing every crease in his gray blanket before the warden inspects his room.

Castón, 45, gets ready for his day not as an inmate convicted of first-degree murder in a killing nearly three decades ago, but as a newly elected city official with a few months left behind bars. He is the city’s first incarcerated person to win an election.

Like most Advisory Neighborhood Commission members — who serve to connect and provide input from their community to the D.C. Council — the responsibilities are tacked on to other work. Castón’s public service is voluntary, dragging his day into the late hours of the night.

But unlike his colleagues who attend meetings or visit constituents, Castón can’t leave his housing unit and constituents can’t visit him. Instead, they contact him through the jail’s mailing system. He works on a schedule set by the jail.He was sentenced to life in prison. Then he won a seat in D.C. government.On June 15, Joel Castón became the District’s first incarcerated person to serve in public office. He hopes to be an advocate for the prison population. (Hadley Green/The Washington Post)

His new duties behind bars and his release in a few months are a reflection of the District’s sweeping criminal justice changes since 2017. Castón is one of dozens of inmates who may have their sentences reduced under the Incarceration Reduction Amendment Act. A subsequent amendment passed by D.C. lawmakers last year extended the law to inmates who committed offenses at age 24 or younger, which included Castón.

As a teen he killed a man. A new law has given him a second chance.

As of 2020, 53 people — most of whom were convicted of murder — were released early.

Even his rise to public office, a saga that began two years ago, is thanks to legislation passed in July 2020 that allows incarcerated people to vote. While Republican legislators across the nation have proposed scaling back voting rights, several states have worked to expand voting rights to current and formerly incarcerated people. For legislators across the nation, Castón’s story provides a glimpse into the effect of those reforms.

Like the other 20 people in his housing unit, Castón wears a gray polo shirt and tan pants.

He reads through instructional books on finance and trading. He catches up with the latest edition of the Wall Street Journal — which tends to be a week behind — as Bloomberg Radio or classical music plays in the background. On his desk recently sat a newspaper reporting the Florida condo collapse, which had happened several days earlier.

By 8 a.m., he retreats to morning yoga next to an office space the Department of Corrections modified for him to perform his elected duties. An hour later, the housing unit comes alive.

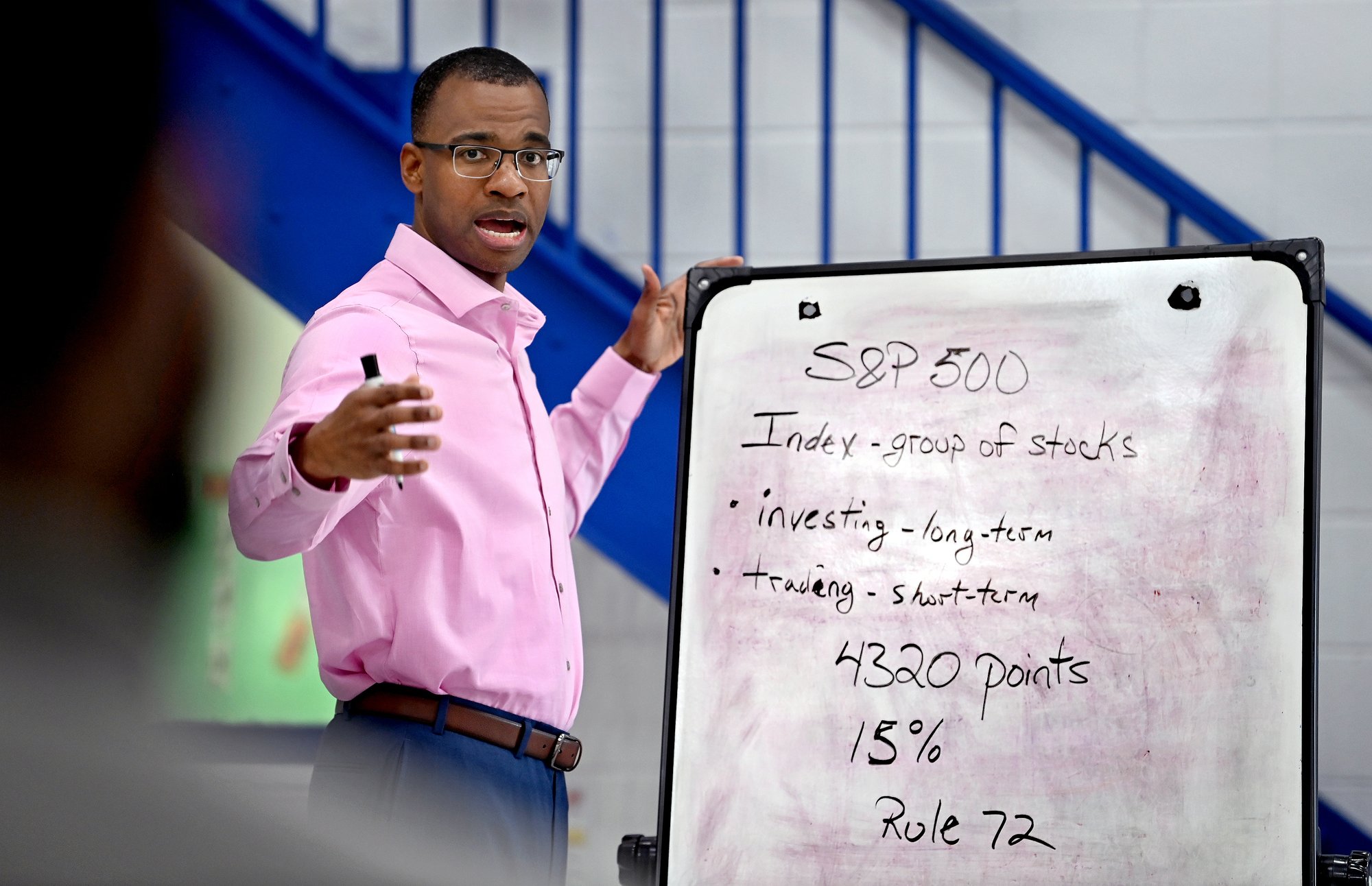

Castón joins others in setting up chairs in a common space decorated with pictures of the unit’s successes in a program focused on rehabilitation and youth mentorship. In the corner near a barred window, inmates tend to the house plants. They each grab a notebook and prepare for the daily briefing — a time to share ambitions and daily reflections. Once a week, Castón leads a lesson on financial literacy.

By 10 a.m., his workday begins. He heads to his office, which houses a desk, a landline phone, a computer with Windows 10, a TV monitor, a microwave and inspirational posters. Colorful sticky notes with reminders and crossed-out obligations line his desk. The equipment, down to the area rug and the professional clothing he wears on special occasions, is provided by the Department of Corrections.

“If the plan doesn’t work, change the plan but never the goal,” reads a sign near his desk.

He normally keeps the office door open, but will close it to take calls when it gets particularly noisy, such as during community-building activities like cornhole bag-toss games.

Castón sometimes is perplexed by the technology that forms the basis of his work. Sending Zoom links feels like learning a new language, and scheduling work tasks into his busy life requires the aid of two others, Darnell Savoy and KayVaughn Brown, who live in the unit.

Castón said other ANC commissioners have reached out to offer guidance. And while he is still hammering out the logistics to stay in touch with his constituents, neighborhood activists have lent a hand in connecting him with residents in the luxury apartment complex across the street and a nearby women’s shelter.

Daniel Rico, a resident of the Park Kennedy apartment complex, said he plans to reach out to Castón virtually.

“This particular ANC neighborhood is at a crossroads of a very different and divided city,” Rico said. “He can be the voice of long-ignored voices, not only to ensure Park Kennedy residents are heard but also the residents of the jail system.”

In his spare time, Castón calls his mother, Mattie Castón, from the case manager’s office on the second floor of the housing unit — one of the perks he and the others enjoy in the Young Men Emerging unit.

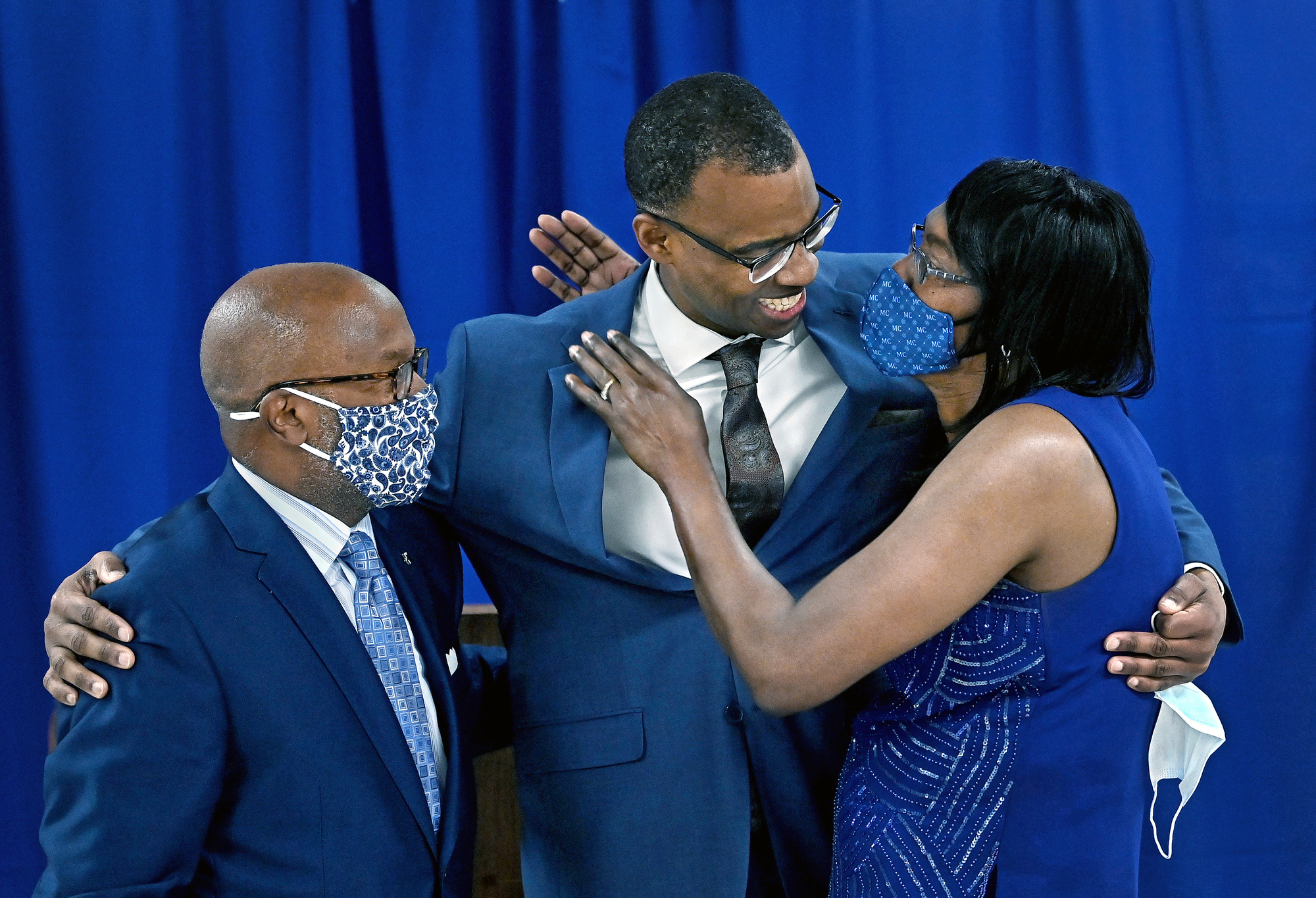

The last time he saw her, he had made a grand entrance into a room at the D.C. Jail one Tuesday evening. There, local officials, family and friends had erupted in cheers as he was to be sworn in.

For this night, he traded his gray polo and tan pants for a blue suit provided by the Department of Corrections. He locked eyes with his mother, who he refers to as his queen, and opened his arms for an embrace.

After a year of being unable to meet face-to-face because of the pandemic, they embraced for the first time — his head resting on hers. The blue sequins from her dress shimmered and danced across the white walls. It was the first moment of many that let him know his life was about to change as a newly elected commissioner.

“I am humbled,” Castón said, echoing the sentiment shared by city officials and advocates who spoke before him that history was being made. “I’ll be the first to admit that I cannot do this alone. We have been voiceless for far too long.”

When he walked to the lectern at his swearing-in ceremony, inmates watched from a monitor inside the facility. They cheered.

“He didn’t have the easiest childhood growing up, but I always knew that he had the potential to do what he’s doing now,” Mattie Castón said in an interview.

By the time he was in the sixth grade, Castón’s parents had separated because of issues stemming from his father’s alcohol abuse, according to court records. Gun violence and drugs later made their mark on his community. He became numb to those aspects of his life in the city’s Ward 8, court records state. Castón began dealing drugs with his cousins at age 12.

By 15, a fire had destroyed his house and left his family homeless.

In November 1994, 18-year-old Castón was charged with first-degree murder in the shooting death of Rafiq Washington. Two years later, he was sentenced to 35 years to life.

Akelo Washington, Rafiq’s brother, said his family did not want to comment about the case.

While incarcerated, Castón earned a GED, led a jail newspaper, started the mentoring unit, became a published author, wrote papers on criminal justice reform, took dozens of courses — some of which were hosted at Georgetown University — and became a financial literacy instructor. He was granted parole in April, with a release date in December. Castón also filed a motion to attempt to push forward his release.

The effort caught the attention of Kim Kardashian West, who described Castón in a motion for his early release as “a leader who sets a positive example for everyone around him. … I found Joel to be intelligent, gracious, respectful, engaging and inspiring.”

Despite the long hours, Castón said he would not trade them for anything. He said his work is part of a mission to enfranchise and change the narrative of incarcerated people.

“Experience is the best teacher, but sometimes experience can take up your life,” he said. Asked what advice he would give to young people, he added: “Listen to their mentors and identify individuals who want to help them in their lives.”

In addition to his ANC work, Castón will take on a job upon his release as a consultant working with the Justice Policy Institute, a nonprofit dedicated to reforming the justice system. He said he also hopes to reconnect with his 25-year-old daughter.

For now, he adjusts his glasses, while crossing off tasks on his to-do list.

SOURCE: The Washington Post