Insight: The Regionalization Of The Cabo Delgado Insurgency Leaves Tanzania Vulnerable

Insight by Evarist Chahali, intelligence analyst.

On 05 October 2017, well organized attacks in Cabo Delgado (Mozambique) gave way to warning calls that Southern Africa has crossed the threshold into an Islamist organized extremist footprint. The purpose of th insight is not to provide an in-depth historical account of attacks, but focussing on the implications for Tanzania and regional counter offensives (SAMIM).

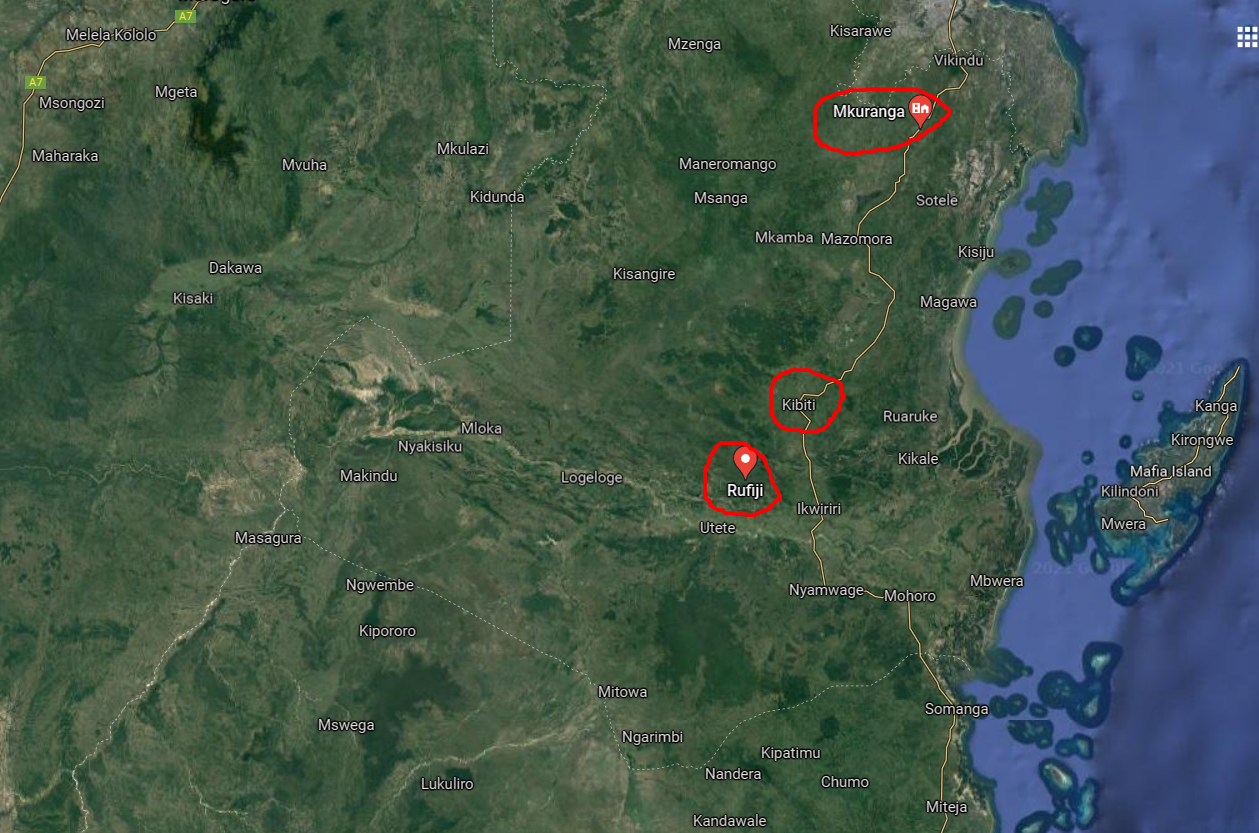

The “MKIRU” Killings:

“MKIRU”, an acronym for Mkuranga, Kibiti and Rufiji, three districts in the Coast Region, where between January 2015 to July 2017, witnessed a spate of killings, with forty fatalities, fifteen of whom were members of the Tanzania Police Force. The rest were either local government officials or ruling party CCM leaders.

The “official” (government) narrative:

On June 25, 2017 IGP Sirro indicated that Tanzanian forces were in the dark on the identity of the assailants. This narrative shifted with a statement on July 5, with the the police chief accusing foreign elements responsible for the attacks.

Earlier, on June 10, the then Home Affairs Minister, Mwigulu Nchemba played politics, alleging a possibility of involvement of opposition parties in the killings.

10 days later, then President, late John Magufuli spoke against calls to let free jailed clerics from a local Islamic group, known as UAMSHO[i], who were facing terrorism charges, saying such appeals were misplaced because of what was happening at MKIRU.

Over a month later, in August 24, IGP Sirro speaking to a local radio station claimed that the assailantshad arrived from other parts (did not say whether local or foreign) about a decade ago, and intermingled with the locals before they started a series of killings.

The locals’ narrative:

Although no group had claimed responsibility for the killings, available evidence suggested that there were strong anti-police sentiments, with the locals accusing the police of brutality.

An incident on January 25, 2013 in which the police arrested and tortured a suspect, Athumani Hamis, to death, led to some of the locals to storm a police station and threatened to set it afire, and when they couldn’t they torched a policeman’s home and destroyed several others’ properties.

Also, at the height of the MKIRU killings, a handwritten message which was doing rounds on social media, stated that “Tunawatangazia wananchi tumewaua hawa kwa sababu wanadhulumu watu…Sisi tumejitolea kufa kuliko kuishi…Hakuna njia ya kumaliza dhuluma isipokuwa chuma tu, hapa chuma tuuu!”[ii](We are informing the locals that we have killed these people because of their injustices towards people…We are willing to sacrifice our lives…There is no way to bring these injustices to an end except bullets).

The government’s response:

Little is known about a joint security operations involving members of Tanzania People’s Defence Forces (TPDF), Tanzania Intelligence and Security Services (TISS) and the Police Force as a government’s response to the killings. However, when reports started to emerge in August 2017 of dead bodies found tied in bags on Indian Ocean shores, suspicions were rife that the dead were victims of the operations.

In November, IGP Sirro was quoted as saying more than 1,300 MKIRU schoolchildren were missing. Had they been killed, or had they sought refuge elsewhere?

On May 05, 2018 Opposition Leader Zitto Kabwe urged the government to come clean about “more that 380 who were missing at MKIRU.” He said he was aware of the ongoing security operations, but they were not conducted within the law and were characterised by human-rights violations, including torture and extrajudicial killings.

Perfect storm?

Hardly a year since he became president, late Magufuli was already being accused of discriminating Muslims in Tanzania. His 2020 cabinet of forty-six had only 7 Muslim ministers. However, the grievances were largely muted due to his authoritarian rule.

Contacts with knowledge of what actually happened at MKIRU in relation to the security operations accuse Magufuli of conducting a massacre against Muslims. A reliable contact added that more than five hundred people were killed during the operation.

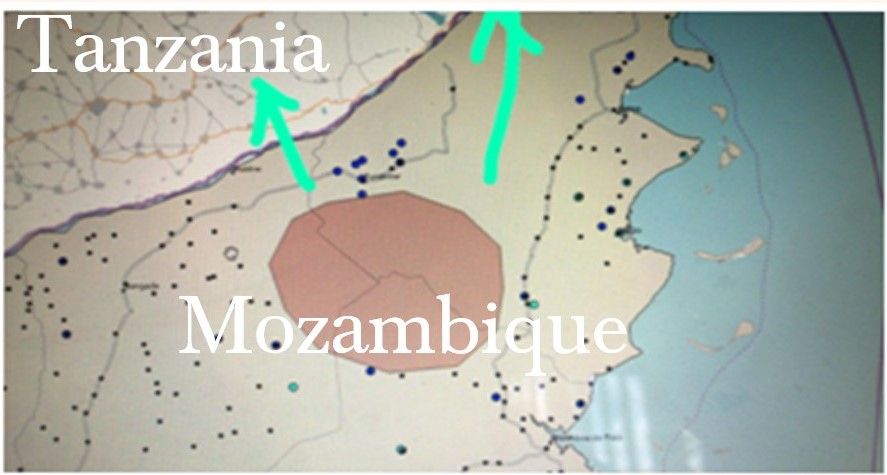

In October 2018, IGP Sirro stated that some of the those who were involved in MKIRU killings have fled to Mozambique. Given the historical and religious connection between the coastal and southern region of Tanzania and Northern Mozambique, and an Islamic insurgency which was well underway by 2017, the latter offered ideal refuge for those fleeing from MKIRU.

Over the past several years, Tanzania has served as an origin and transit point for radicalized individuals fighting alongside terrorist groups operating in nearby countries, particularly al-Shabaab in Somalia. However, the East African nation has not been as internally affected by jihadist groups as nearby Mozambique, Kenya, and Somalia.

Nonetheless, what happened at MKIRU, and the recent developments in Cabo Delgado where the SADC, Rwandan and Mozambique are making considerable gains, such as the killing of insurgents’ leader Sheikh Njile and 18 fighters, and the troops have reclaimed nearly all areas that were seized by militants in Cabo Delgado province against the insurgents, it is likely only a matter of time before the threat increasingly turns towards Tanzania.

Conclusion:

Will the insurgency expand into Tanzania?

We assess an expansion is plausible given the historical context of close associations, a porous border that allows for unaccounted movements of people and goods. Paramount is a security forces struggling to gain confidence among locals, therewith limiting access to intelligence.

Is the current militarized strategy effective?

Irrespective the need for security operations, human rights violations, people accused of abetting insurgents merely derived from perceptions and communities refraining from any engagements with security forces leaves security operations oppressive in perception. These operations will only have limited impact if not adjusted.

What does the future hold?

Current counter offensive successes are not addressing the root causes of the insurgency. A similar situation prevails in the border area between Tanzania and Mozambique. We assess that Tanzania will remain vulnerable to insurgent presence and attacks, with no indication of a change in security operation strategies. Entrenched contractual interests, a deep seated historical context of Frelimo versus Renamo (Mozambique as a post war state) and an ever emergent transnational crisis evolving in Cabo Delgado advances more concerns than optimism.

Footnotes:

[i]Uamsho, (“awaking” in Swahili), also known as the Association for Islamic Mobilization and Propagation, is a now-defunct Islamist separatist group in Zanzibar. Founded in 2002, the group sought the archipelago’s secession from mainland Tanzania and called for a constitution based on sharia. Its leader, Sheikh Farid Hadi Ahmed, demanded a dress code for foreigners and limitations on the consumption of alcohol.

Many of the group’s key leaders were arrested as terrorist suspects in 2012. That May, following a spate of arrests, hundreds of Uamsho members in Zanzibar’s Stone Town clashed with police and set two churches on fire. Zanzibari authorities arrested Uamsho leader Farid Hadi Ahmed that October, leading to riots in Stone Town during which a suspected Uamsho member hacked a policeman to death with machetes.

[ii] https://www.mwananchi.co.tz/mw/habari/kitaifa/ujumbe-wa-kuua-polisi-zaidi-waazidisha-hofu-kibiti-2854608 (Accessed on 05.10.2021)